Influenza A virus subtype H7N9

| Influenza A virus subtype H7N9 | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | Influenza A virus |

| Serotype: | Influenza A virus subtype H7N9 |

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

| Types

|

| Vaccines |

| Treatment

|

|

'

Influenza A virus subtype H7N9 (A/H7N9) is a subtype of the influenza A virus, which causes influenza (flu), predominantly in birds. It is enzootic (maintained in the population) in many bird populations.[1] A/H7N9 virus is shed in the saliva, mucous, and feces of infected birds.[2] The virus can spread rapidly through poultry flocks and among wild birds; it can also infect humans that have been exposed to infected birds.[2]

A/H7N9 virus is shed in the saliva, mucous, and feces of infected birds; other infected animals may shed bird flu viruses in respiratory secretions and other body fluids.[3] The virus can spread rapidly through poultry flocks and among wild birds.[3]

Symptoms of A/H7N9 influenza vary according to both the strain of virus underlying the infection and on the species of bird or mammal affected.[4][5] Classification as either Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI) or High Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) is based on the severity of symptoms in domestic chickens and does not predict the severity of symptoms in humans.[6] Chickens infected with LPAI A/H7N9 virus display mild symptoms or are asymptomatic, whereas HPAI A/H7N9 causes serious breathing difficulties, a significant drop in egg production, and sudden death.[7]

In mammals, including humans, A/H7N9 influenza (whether LPAI or HPAI) is rare; it can usually be traced to close contact with infected poultry or contaminated material such as feces.[8] Symptoms of infection vary from mild to severe, including fever, diarrhoea, and cough; the disease can often be fatal.[9][10]

The A/H7N9 virus is considered to be enzootic (continually present) in wild aquatic birds, which may carry the virus over large distances during their migration.[11] The first known case of A/H7N9 influenza infecting humans was reported in March 2013, in China.[12] Cases continued to be recorded in poultry and humans in China over the course of the next 5 years. Between February 2013 and February 2019 there were 1,568 confirmed human cases and 616 deaths associated with the outbreak in China.[13] Initially the virus was low pathogenic to poultry, however around 2017 a highly pathogenic strain developed which became dominant. The outbreak in China has been partially contained by a program of poultry vaccination which commenced in 2017.[14]

Bird-adapted A/H7N9 transmits relatively easily from poultry to humans, although human to human transmission is rare. Its ability to cross the species barrier renders it a potential pandemic threat, especially if it should acquire genetic material from a human-adapted strain.[15][16]

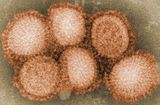

Virology

H7N9 is a subtype of Influenza A virus. Like all subtypes it is an enveloped negative-sense RNA virus, with a segmented genome.[17] Influenza viruses have a relatively high mutation rate that is characteristic of RNA viruses.[18] The segmentation of its genome facilitates genetic recombination by reassortment in hosts infected with two different strains of influenza viruses at the same time.[19][20] Through a combination of mutation and genetic reassortment the virus can evolve to acquire new characteristics, enabling it to evade host immunity and occasionally to jump from one species of host to another.[21][22]

Epidemiology

Most human infections with avian influenza viruses, including A/H7N9, occur after exposure to infected poultry or contaminated environments. A/H7N9 viruses continue[when?] to circulate in poultry in China. Most reported patients with A/H7N9 virus infection have had severe respiratory illness (e.g., pneumonia). Rare instances of limited person-to-person spread of this virus have been identified in China, but there is no evidence of sustained person-to-person spread.[citation needed] Some human infections with A/H7N9 virus have been reported outside of mainland China, Hong Kong or Macao but all of these infections have occurred among people who had traveled to China before becoming ill. A/H7N9 viruses have not been detected in people or birds in the United States.[23]

History

Outbreak in China, 2013-2019

Prior to 2013, A/H7N9 had previously been isolated only in birds, with outbreaks reported in the Netherlands, Japan, and the United States. Until the 2013 outbreak in China, no human infections with A/H7N9 had been reported.[8][24]

A significant outbreak of Influenza A virus subtype H7N9 (A/H7N9) started in March 2013 when severe influenza affected 18 humans in China; six subsequently died.[15] It was discovered that a low pathogenic strain of A/H7N9 was circulating among chickens, and that all the affected people had been exposed in poultry markets. Further cases among humans and poultry in mainland China continued to be identified sporadically throughout the year, followed by a peak around the festival season of Chinese New Year (January and February) in early 2014 which was attributed to the seasonal surge in poultry production. Up to December 2013, there had been 139 cases with 47 deaths.[25]

Infections among humans and poultry continued during the next few years, again with peaks around the new year. In 2016 a virus strain emerged which was highly pathogenic to chickens.[14][26] In order to contain the HPAI outbreak, the Chinese authorities in 2017 initiated a large scale vaccination campaign against avian influenza in poultry. Since then, the number of outbreaks in poultry, as well as the number of human cases, dropped significantly. In humans, symptoms and mortality for both LPAI and HPAI strains have been similar.[14] Although no human H7N9 infections have been reported since February 2019, the virus is still circulating in poultry, particularly in laying hens. It has demonstrated antigenic drift to evade vaccines, and remains a potential threat to the poultry industry and public health.[26]

Genetic characterisation of this strain of avian influenza A/7N9 shows that it was not related to A/H7N9 strains previously identified in Europe and North America. This new strain resulted from the recombination of genes between several parent viruses noted in poultry and wild birds in Asia. The H7 gene is most closely related to sequences found in samples from ducks in Zhejiang province in 2011.The N9 gene was closely related to isolated wild ducks in South Korea in 2011. Other genes resembled samples collected in Beijing and Shanghai in 2012. The genes would have been carried along the East Asian flyway by wild birds during their annual migration.[27][28][27][29]

The genetic characteristics of A/H7N9 virus are of concern because of their pandemic potential, e.g. their potential to recognise human and avian influenza virus receptors which affects the ability to cause sustained human-to-human transmission, or the ability to replicate in the human host.[15][14]

Other occurrences

During early 2017, outbreaks of avian influenza A(H7N9) occurred in poultry in the USA. The strain in these outbreaks was of North American origin and is unrelated to the Asian lineage H7N9 which is associated with human infections in China.[30]

In May 2024, an HPAI A/H7N9 was detected on a poultry farm with 160,000 birds in Terang, Australia. There were 14,000 clinically affected birds. It is presumed that migratory wild birds were the source of the outbreak.[31]

Symptoms

Avian flu viruses, both HPAI and LPAI, can infect humans who are in close, unprotected contact with infected poultry. Incidents of cross-species transmission are rare, with symptoms ranging in severity from no symptoms or mild illness, to severe disease that resulted in death.[32][33] As of February, 2024 there have been very few instances of human-to-human transmission, and each outbreak has been limited to a few people.[34] All subtypes of avian Influenza A have potential to cross the species barrier, with H5N1 and H7N9 considered the biggest threats.[35][36]

As of 2019, the case fatality rate of the Chinese strain of A/H7N9 is 39%.[37]

Transmission

Information released in 2014 indicated that 75% of those that came down with H7N9 influenza had previously been exposed to domestic poultry, often in live bird markets.[38][39] However, Chinese scientists found evidence that person-to-person transmission was possible, but would not transmit easily.[40]

Vaccine

Although China has been praised for its quick response,[12] some experts believe that there would be great difficulty providing adequate supplies of a vaccine if the virus were to develop into a pandemic. According to an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in May 2013, "Even with additional vaccine manufacturing capacity... the global public health community remains woefully underprepared for an effective vaccine response to a pandemic...There is no reason to believe that a yet-to-be-developed pandemic A(H7N9) vaccine will perform any better than existing seasonal vaccines or the A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccines [about 60% to 70% effectiveness], particularly with regard to vaccine efficacy in persons older than 65 years."[41]

On October 26, 2013, Chinese scientists announced that they had successfully produced an H7N9 vaccine, the first influenza vaccine to be developed entirely in China.[42] It was developed jointly by researchers from Zhejiang University, Hong Kong University, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China's National Institute for Food and Drug Control, and the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Chinese National Influenza Center director Shu Yuelong said the vaccine passed tests on ferrets and had been approved for humans, but H7N9 has not spread far enough to merit widespread vaccination. The vaccine was developed from a throat swab of an infected patient taken April 3.[43]

On November 12, 2013, US scientists at Novavax, Inc. announced their successful clinical testing of an H7N9 vaccine in the New England Journal of Medicine. They had previously described the development, manufacture, and efficacy in mice of an A/Anhui/1/13 (H7N9) viruslike particle (VLP) vaccine produced in insect cells with the use of recombinant baculovirus. The vaccine combined the HA and neuraminidase (NA) of A/Anhui/1/13 with the matrix 1 protein (M1) of A/Indonesia/5/05. The study enrolled 284 adults (≥18 years of age) in a randomized, observer-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial of this vaccine.[44]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began sequencing and development of a vaccine as routine procedure for any new transgenic virus.[45] The CDC and vaccine manufacturers are developing a candidate virus to be used in vaccine manufacturing if there is widespread transmission.[8][46] On September 18, 2013, NIH announced that researchers have begun testing an investigational H7N9 influenza vaccine in humans. Two Phase II trials are collecting data about the safety of the vaccine, immune system responses to different vaccine dosages, both with and without adjuvants. Healthy adults 19 to 64 years of age will be enrolled in the two studies. The inactivated-virus vaccine was made with H7N9 virus that was isolated in Shanghai, China. Adjuvants are being tested with the vaccine to determine if an adequate immune response can be produced. In addition, during a pandemic, adjuvants may be used as part of a "dose-sparing strategy".[47]

In response to a request from the CDC and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, following the unprecedented immediate release of the H7N9 flu virus gene sequences from the first human cases, by scientists at the China CDC[48] through the GISAID Initiative,[49][50] the J. Craig Venter Institute, and Synthetic Genomics Vaccines, Inc. began working with Novartis to synthesize the genes of the new viral strain, and supplied these synthesized genes to the CDC.[51][52][53]

Reactions

The scientific community has praised China for its transparency and rapid response to the outbreak of H7N9.[54] In an editorial on April 24, 2013, the journal Nature said "China deserves credit for its rapid response to the outbreaks of H7N9 avian influenza, and its early openness in the reporting and sharing of data."[12] This, in spite of initial worries by Chinese scientists and officials that they might lose credit for their work in isolating and sequencing the novel H7N9 virus, after learning that pharmaceutical company Novartis and the J. Craig Venter Institute had used their sequences to develop US-funded H7N9 vaccine without offering to collaborate with the Chinese team, according to Nature.[55] They believed, the usage of their data was initially not handled in the spirit of the GISAID sharing mechanism, which requires scientists who use the sequences to credit and propose collaboration with those who deposited the data in GISAID. Nature cited a Chinese official who concluded that this situation was quickly mitigated once communication channels were opened and the parties agreed to collaborate, thanks to GISAID president Peter Bogner.[56][57]

Despite concerns that vaccination of poultry against the H5N1 avian influenza virus over the last decade might have made it harder for Chinese veterinary technicians to spot the recent spread of the H7N9 virus, China's Agriculture Ministry defended its policy of large-scale vaccination of poultry against the earlier bird flu strain, saying that it was not interfering with its efforts now to identify the emerging H7N9 virus.[58]

On April 15, 2013, the RIWI Corporation, led by researcher Neil Seeman of the University of Toronto released data on 7,016 Chinese “fresh” (i.e. non-panel based) Internet users – with a 24.08% response rate – over 20 hours. The level of contagion awareness was 31% in Beijing, 38% in Hangzhou, 33% in Nanjing, 40% in Shanghai, 52% in Ürümqi, and 28% in Zhengzhou (Chi Square; P = 0.05). The result far exceeds that of other internet surveys, suggesting an intense relevancy of interest and sense of urgency related to the current disease outbreak in the minds of average Chinese citizens.[59]

Efforts to prevent spread of disease

In April 2013, Shanghai's health ministry ordered culling of birds after pigeon samples collected at the Huhuai wholesale agricultural products market in Songjiang District of Shanghai showed H7N9[60][61] On April 4, 2013, Shanghai authorities closed a live-poultry-trading zone and began slaughtering all birds. Poultry trading areas in two other areas of the Minhang district were also closed.[62] On April 6, 2013, all Shanghai live poultry markets closed temporarily in response to the H7N9 found in the pigeon samples.[8][60][63] The same day, Hangzhou also closed its live poultry markets.[63]

After gene sequence analysis, the national avian flu reference laboratory concluded that the strain of the H7N9 virus found on pigeons was highly congenic with those found on persons infected with H7N9 virus, the ministry said.[61] On April 22, 2013, Forbes quoted Chinese state media reporting $2.7 billion in poultry industry losses.[64]

When January 2014 brought a dramatic increase in reports of disease, the Chinese government responded by halting live poultry trading in three cities in Zhejiang province where 49 cases and 12 deaths had been reported. In addition, live poultry trading in Shanghai was halted for three months. In Hong Kong, authorities reacted to the discovery of H7N9 in live chickens from the province of Guangdong by suspending imports of fresh poultry from mainland China for 21 days, culling 20,000 chickens, and other measures in an effort to control the spread of the virus.[65]

On February 18, 2014, it was announced that the Chinese government would extend the ban for four months. The health minister also said that they plan to prevent diseased birds from entering the market by setting up a facility where imported poultry can be quarantined to ensure they are disease-free.[66]

International response

The WHO did not advise against travel to China at that point in time, as there was no evidence of human-to-human transmission of the virus.[67]

- United States

On April 9, 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) activated its Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in Atlanta at Level II, the second-highest level of alert.[68] Activation was prompted because the novel H7N9 avian influenza virus has never been seen before in animals or humans and because reports from China have linked it to severe human disease. EOC activation will "ensure that internal connections are developed and maintained and that CDC staff are kept informed and up to date with regard to the changing situation."[69]

- Canada

On April 10, 2013, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) spelled out bio-safety guidance for handling the H7N9 virus.[70] They stated that work with live cultures must be conducted in biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) containment. They also said that studies growing H7N9 virus should not be done in labs that culture human influenza viruses and that personnel should not have contact with susceptible animals for 5 days after handling H7N9 samples.[71]

- Malaysia

Malaysia announced that it would temporarily ban Chinese chicken imports.[72]

- Vietnam

Vietnam announced that it would temporarily ban Chinese poultry imports.[73][74]

- Singapore

All hospitals were informed to remain vigilant, and to notify Singapore's Ministry of Health (MOH) immediately of any suspected cases of avian influenza in individuals who have recently returned from affected areas in China.[67] MOH advised returning travellers from affected areas in China (Shanghai, Anhui, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang) to look out for signs and symptoms of respiratory illness, such as fever and cough, and seek early medical attention if they are ill with such symptoms.[67] MOH also advised individuals to inform their doctors of their travel history, should they develop these symptoms after returning to Singapore.[67]

- Taiwan

On 3 April 2013, the Executive Yuan activated Taiwan's Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC) in response to the epidemic in mainland China.[75][76] The Executive Yuan deactivated the CECC for H7N9 influenza on 11 April 2014.[75]

During this period, 24 meetings were convened with representatives from 24 central government agencies including the Council of Agriculture, the Ministry of Transportation and Communications, and the Ministry of Education, along with 22 city and county governments. Meetings were attended by regional commanding officers and deputy commanding officers of the Communicable Disease Control Network.[75]

On 17 May 2013, a ban became effective on the slaughtering of live poultry at traditional wet markets, which eliminated the risk of animal-to-human transmission of avian influenza.[75]

See also

- Antigenic shift

- Influenza A virus subtype H9N2

- Influenza A virus subtype H5N1

- Pandemic H1N1/09 virus

- Influenza research

- Zoonosis

References

- ^ "Influenza (Avian and other zoonotic)". who.int. World Health Organization. October 3, 2023. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ a b "Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Bird Flu Viruses in People | Avian Influenza (Flu)". cdc.gov. US: Centers for Disease Control. April 19, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "Prevention and Antiviral Treatment of Bird Flu Viruses in People | Avian Influenza (Flu)". cdc.gov. US: Centers for Disease Control. April 19, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ "Bird flu (avian influenza)". betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Victoria, Australia: Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ^ "Avian influenza: guidance, data and analysis". gov.uk. November 18, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ^ "Avian Influenza in Birds". cdc.gov. US: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 14, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ "Bird flu (avian influenza): how to spot and report it in poultry or other captive birds". gov.uk. UK: Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs and Animal and Plant Health Agency. December 13, 2022. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Frequently Asked Questions on human infection with influenza A(H7N9) virus, China". World Health Organization. April 5, 2013. Archived from the original on February 13, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ "Avian Influenza A(H7N9) virus". Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. June 1, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Avian influenza: guidance, data and analysis". gov.uk. November 18, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ^ Joseph U, Su YC, Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ (January 2017). "The ecology and adaptive evolution of influenza A interspecies transmission". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 11 (1): 74–84. doi:10.1111/irv.12412. PMC 5155642. PMID 27426214.

- ^ a b c "The fight against bird flu". Nature. 496 (7446): 397. April 24, 2013. doi:10.1038/496397a. PMID 23627002.

- ^ CDC (June 3, 2024). "2010-2019 Highlights in the History of Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) Timeline". Avian Influenza (Bird Flu). Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Risk assessment of avian influenza A(H7N9) – eighth update". UK Health Security Agency. January 8, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Factsheet on A(H7N9)". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. June 15, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ Tanner, W. D.; Toth, D. J. A.; Gundlapalli, A. V. (December 2015). "The pandemic potential of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus: a review". Epidemiology & Infection. 143 (16): 3359–3374. doi:10.1017/S0950268815001570. ISSN 0950-2688. PMC 9150948. PMID 26205078.

- ^ "Influenza A Subtypes and the Species Affected | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 13, 2024. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Márquez Domínguez L, Márquez Matla K, Reyes Leyva J, Vallejo Ruíz V, Santos López G (December 2023). "Antiviral resistance in influenza viruses". Cellular and Molecular Biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France). 69 (13): 16–23. doi:10.14715/cmb/2023.69.13.3. PMID 38158694.

- ^ Kou Z, Lei FM, Yu J, Fan ZJ, Yin ZH, Jia CX, Xiong KJ, Sun YH, Zhang XW, Wu XM, Gao XB, Li TX (2005). "New Genotype of Avian Influenza H5N1 Viruses Isolated from Tree Sparrows in China". J. Virol. 79 (24): 15460–15466. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.24.15460-15466.2005. PMC 1316012. PMID 16306617.

- ^ The World Health Organization Global Influenza Program Surveillance Network. (2005). "Evolution of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in Asia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (10): 1515–1521. doi:10.3201/eid1110.050644. PMC 3366754. PMID 16318689. Figure 1 shows a diagramatic representation of the genetic relatedness of Asian H5N1 hemagglutinin genes from various isolates of the virus

- ^ Shao, Wenhan; Li, Xinxin; Goraya, Mohsan Ullah; Wang, Song; Chen, Ji-Long (August 7, 2017). "Evolution of Influenza A Virus by Mutation and Re-Assortment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (8): 1650. doi:10.3390/ijms18081650. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 5578040. PMID 28783091.

- ^ Eisfeld AJ, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y (January 2015). "At the centre: influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 13 (1): 28–41. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3367. PMC 5619696. PMID 25417656.

- ^ Asian Lineage Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ Schnirring, Lisa (April 1, 2013). "China reports three H7N9 infections, two fatal". CIDRAP News. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ Li, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, M.; Chen, Z.; Li, F.; Wu, H.; Xiang, N.; Chen, E.; et al. (April 24, 2013). "Preliminary Report: Epidemiology of the Avian Influenza A (H7N9) Outbreak in China". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (6): 520–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1304617. PMC 6652192. PMID 23614499.

- ^ a b Liu, Yang; Chen, Yuhua; Yang, Zhiyi; Lin, Yaozhong; Fu, Siyuan; Chen, Junhong; Xu, Lingyu; Liu, Tengfei; Niu, Beibei; Huang, Qiuhong; Liu, Haixia; Zheng, Chaofeng; Liao, Ming; Jia, Weixin (June 2024). "Evolution and Antigenic Differentiation of Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus, China". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 30 (6): 1218–1222. doi:10.3201/eid3006.230530. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 11138980. PMID 38640498.

- ^ a b Schnirring, Lisa (May 2, 2013). "H7N9 gene tree study yields new clues on mixing, timing". CIDRAP News. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Liu, D.; Shi, W.; Shi, Y.; Wang, D.; Xiao, H.; Li, W.; Bi, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. (2013). "Origin and diversity of novel avian influenza A H7N9 viruses causing human infection: phylogenetic, structural, and coalescent analyses". The Lancet. 381 (9881): 1926–1932. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60938-1. PMID 23643111. S2CID 32552899.

- ^ Koopmans, M.; De Jong, M. D. (2013). "Avian influenza A H7N9 in Zhejiang, China". The Lancet. 381 (9881): 1882–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60936-8. PMID 23628442. S2CID 11698168.

- ^ "Risk assessment of avian influenza A(H7N9) – eighth update". UK Health Security Agency. January 8, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ "Preliminary Outbreak Assessment - Highly pathogenic avian influenza (H7N3 and H7N9) in poultry in Australia" (PDF). Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. June 17, 2024. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ CDC (May 30, 2024). "Avian Influenza A Virus Infections in Humans". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Questions and Answers on Avian Influenza". An official website of the European Commission. June 11, 2024. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Reported Human Infections with Avian Influenza A Viruses | Avian Influenza (Flu)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 1, 2024. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Zoonotic influenza". Wordl Health Organization. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "The next pandemic: H5N1 and H7N9 influenza?". Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ "Risk assessment of avian influenza A(H7N9) – eighth update". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Emerg Infect Dis. Possible Role of Songbirds and Parakeets in Transmission of Influenza A(H7N9) Virus to Humans". FluTrackers - News and Information. January 24, 2014. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ "OIE expert mission finds live bird markets play a key role in poultry and human infections with influenza A(H7N9)". Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health. April 30, 2013. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Evidence suggests new bird flu spread among people". USAToday. August 6, 2013. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ "Experts offer dim view of potential vaccine response to H7N9". May 10, 2013. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ^ "Chinese researchers develop H7N9 flu vaccine". Xinhua. October 26, 2013. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ "Chinese develop vaccination for H7N9, bird flu". UPI. October 26, 2013. Archived from the original on October 31, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ "New England Journal of Medicine Publishes Positive Data From Clinical Trial of Novavax' Vaccine Against H7N9 Avian Flu" (PDF). Novavax. November 13, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015.

- ^ CDC.GOV H7N9 Portal, September 20, 2018, archived from the original on April 29, 2013, retrieved February 24, 2017

- ^ Roos, Robert (April 5, 2013). "CDC working on vaccine, tests for novel H7N9 virus". CIDRAP News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ NIH.gov/news/health/sep2013/niaid-18

- ^ Gao, Rongbao; Cao, Bin; Hu, Yunwen; Feng, Zijian; Wang, Dayan; Hu, Wanfu; Chen, Jian; Jie, Zhijun; Qiu, Haibo (May 15, 2013). "Human Infection with a Novel Avian-Origin Influenza A (H7N9) Virus" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (20): 1888–1897. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1304459. PMID 23577628. S2CID 17525446. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- ^ Shu, Yuelong; McCauley, John (March 30, 2017). "GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data – from vision to reality". Eurosurveillance. 22 (13): 30494. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es.2017.22.13.30494. PMC 5388101. PMID 28382917.

- ^ Elbe, Stefan; Buckland-Merrett, Gemma (January 1, 2017). "Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID's innovative contribution to global health". Global Challenges. 1 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1002/gch2.1018. ISSN 2056-6646. PMC 6607375. PMID 31565258.

- ^ Hekele, Armin; Bertholet, Sylvie; Archer, Jacob; Gibson, Daniel G.; Palladino, Giuseppe; Brito, Luis A.; Otten, Gillis R.; Brazzoli, Michela; Buccato, Scilla (August 14, 2013). "Rapidly produced SAM® vaccine against H7N9 influenza is immunogenic in mice". Emerging Microbes & Infections. 2 (8): e52. doi:10.1038/emi.2013.54. PMC 3821287. PMID 26038486.

- ^ Dormitzer, Philip R. (2014). "Rapid Production of Synthetic Influenza Vaccines". Influenza Pathogenesis and Control - Volume II. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 386. Springer, Cham. pp. 237–273. doi:10.1007/82_2014_399. ISBN 978-3-319-11157-5. PMID 24996863.

- ^ "Prepared Statement from J. Craig Venter, Ph.D., and the J. Craig Venter Institute and Synthetic Genomics Vaccines, Inc. on the H7N9 avian flu strain in China". J. Craig Venter Institute. April 9, 2013. Archived from the original on April 20, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ "China praised for transparency during bird flu outbreak". CBS News. April 11, 2013. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ Schnirring, Lisa (May 1, 2013). "Second case from Hunan raises H7N9 total to 128". Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy. Archived from the original on May 3, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Declan Butler; David Cyranoski (May 2, 2013). "Flu papers spark row over credit for data". Nature Magazine. 497 (7447): 14–15. Bibcode:2013Natur.497...14B. doi:10.1038/497014a. PMID 23636370.

- ^ Press release no. 108 (April 16, 2013). "Transmissibility of novel avian influenza: GISAID database provides essential data for control strategies". Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bradsher, Keith (April 12, 2013). "China Defends Vaccination of Poultry as Flu Spreads". New York Times. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ "New H7N9 Data: An Epidemic Rising?". RIWI. April 15, 2013. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Mullen, Jethro (April 5, 2013). "Chinese authorities kill 20K birds as avian flu toll rises to 6". CNN. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Fang Yang (April 5, 2013). "Shanghai begins culling poultry; one contact shows flu symptoms". english.news.cn. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Schnirring, Lisa (April 4, 2013). "China reports more H7N9 cases, deaths; virus may be in pigeons". CIDRAP News. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Mungin, Lateef (April 6, 2013). "China closes poultry sale in second city after bird flu outbreak". CNN. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Flannery, Russell (April 22, 2013). "H7N9 Bird Flu Cases In China Rise To 104; Deaths At 21". Forbes. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ "Sorry - this page has been removed". Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2016 – via The Guardian.

- ^ "Pandemic Information News". Archived from the original on February 8, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Ministry of Health closely monitoring the influenza A (H7N9) situation". Singapore Ministry of Health. April 6, 2013. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ "China's new bird flu sickens 38, kills 10". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ Roos, Robert (April 9, 2013). "CDC activates emergency center over H7N9". CIDRAP News. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ^ Public Health Agency of Canada (April 9, 2013). "Joint Biosafety Advisory - Influenza A(H7N9) virus". Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- ^ Schnirring, Lisa (April 15, 2013). "China reports 3 new H7N9 cases, 64 total, 14 deaths". CIDRAP News. Archived from the original on April 29, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ "Malaysia Bans Chicken Imports From China". Wall Street Journal. April 26, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kaiman, Jonathan; Davison, Nicola (April 3, 2013). "China reports nine bird flu cases amid allegations of cover up on social media". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 14, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ^ "Vietnam bans China poultry after new bird flu strain deaths". Brunei Times. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "As Central Epidemic Command Center for H7N9 influenza is deactivated per Executive Yuan's consent, Taiwan CDC continues to closely monitor H7N9 influenza activity". www.cdc.gov.tw. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "新聞發布". Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2020.