South African Class 7B 4-8-0

28+1⁄2 in (724 mm)

34 in (864 mm) retyred

♥ 9 LT 14 cwt (9,856 kg)

♣ 11 LT 2 cwt 2 qtr (11,300 kg)

♥ 11 LT 2 cwt (11,280 kg)

♣ 11 LT 8 cwt (11,580 kg)

♥ 9 LT 8 cwt (9,551 kg)

♣ 9 LT 17 cwt 2 qtr (10,030 kg)

♥ 9 LT 14 cwt (9,856 kg)

♣ 10 LT 4 cwt 3 qtr (10,400 kg)

♥ 9 LT 10 cwt (9,652 kg)

♣ 10 LT 13 cwt (10,820 kg)

♥ 9 LT 8 cwt (9,551 kg)

♣ 11 LT 2 cwt 2 qtr (11,300 kg)

♥ 38 LT (38,610 kg)

♣ 41 LT 16 cwt (42,470 kg)

♥ 49 LT 2 cwt (49,890 kg)

♣ 53 LT 5 cwt 3 qtr (54,140 kg)

♥ 83 LT 4 cwt (84,540 kg)

♣ 87 LT 7 cwt 3 qtr (88,790 kg)

ZA, ZB, ZC, ZE permitted

♣ 17.2 sq ft (1.60 m2)

♥ 6 ft 10 in (2,083 mm)

♣ 7 ft (2,134 mm)

♥ 4 ft 6 in (1,372 mm)

♣ 5 ft (1,524 mm)

♥ 100: 1+7⁄8 in (48 mm)

♣ 200: 2 in (51 mm)

♣ 40 Drummond: 2+1⁄2 in (64 mm)

170 psi (1,172 kPa)

♥♣ 180 psi (1,241 kPa)

♥ 113 sq ft (10.5 m2)

♣ 122.2 sq ft (11.35 m2)

♣ 1,226 sq ft (113.9 m2)

♥ 1,089 sq ft (101.171 m2)

♣ 1,348.2 sq ft (125.25 m2)

23 in (584 mm) stroke

♥ 17+1⁄2 in (444 mm) bore

23 in (584 mm) stroke

AAR knuckle (1930s)

| Performance figures | |

|---|---|

| Tractive effort | ♠ 18,660 lbf (83.0 kN) @ 160 psi (1,103 kPa) 19,810 lbf (88.1 kN) @ 170 psi (1,172 kPa) ♥ 22,240 lbf (98.9 kN) @ 180 psi (1,241 kPa) ♣ 20,990 lbf (93.4 kN) @ 180 psi (1,241 kPa) |

| Factor of adh. | 4.32 |

| Career | |

|---|---|

| Operators | Imperial Military Railways Rhodesia Railways Mashonaland Railways Beira-Mashonaland-Rhodesia Rhodesia Railways Northern Central South African Railways Natal Government Railways South African Railways Zambesi Saw Mills |

| Class | IMR, RR 7th Class NGR Class L CSAR, SAR Class 7B |

| Number in class | 29 IMR & RR 28 SAR |

| Numbers | IMR 106-130 PPR 7-9 RR 19 & 63 CSAR 373-400 NGR 327-329 SAR 949, 1032-1034, 1036-1058 |

| Delivered | 1900 |

| First run | 1900 |

| Withdrawn | 1972 |

The South African Railways Class 7B 4-8-0 of 1900 was a steam locomotive from the pre-Union era in Transvaal.

In 1900, the Imperial Military Railways placed 25 Cape 7th Class 4-8-0 Mastodon type steam locomotives in service. In that same year, three Cape 7th Class locomotives which had been ordered by the Pretoria-Pietersburg Railway were also placed in service. All these locomotives were taken onto the Central South African Railways roster at the end of the Second Boer War in 1902. In 1906, three of these locomotives were sold to the Natal Government Railways.[1][2][3]

In 1912, 26 of these 28 locomotives were assimilated into the South African Railways. They were followed in 1913 by the remaining two, which had been leased to Paulings as construction locomotives. All but one of these locomotives were renumbered and reclassified to Class 7B. In 1915, one more Cape 7th Class locomotive was obtained from the Rhodesia Railways and erroneously also designated Class 7B.[1][2][3][4]

Background

After the outbreak of the Second Boer War in 1899, control of all railways in the Cape of Good Hope and the Colony of Natal remained in the hands of their civil staff, but now working in co-operation with the invading British military. As possession was gradually obtained of the lines of the Orange Free State and the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, the Oranje-Vrijstaat Gouvernement-Spoorwegen (OVGS) and the Nederlandsche-Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg-Maatschappij (NZASM) were combined into the Imperial Military Railways (IMR). The military railway was in the hands of military and civilian staff who were appointed by the Director of Railways for the South African Field Forces, Lieutenant Colonel E.P.C. Girouard KCMG DSO RE.[1]

Manufacturer

Because of the damage caused during hostilities and the transportation demands of the British armed forces, a shortage of locomotives developed. In 1900, the IMR placed an order with Neilson, Reid and Company for 25 Cape 7th Class locomotives which were numbered in the range from 106 to 130 upon delivery.[1][5]

Also in 1900, three Cape 7th Class locomotives which had been ordered before the war by the Pretoria-Pietersburg Railway (PPR), were intercepted by the IMR and placed in service. These engines had also been built by Neilson, Reid. Numbered PPR 7 to 9, these were the last locomotives to have been ordered by the PPR before it ceased to exist upon its incorporation into the NZASM, which itself was subsequently incorporated into the IMR.[1]

One more locomotive in the group which was eventually to become the South African Railways (SAR) Class 7B was part of a batch of Cape 7th Class locomotives which had been built for the Rhodesia Railways (RR) by Neilson, Reid in 1899 and placed in service in Rhodesia in 1900.[1]

The original Cape 7th Class had been designed in 1892 by H.M. Beatty, Cape Government Railways (Western System) Locomotive Superintendent. All these locomotives were built to the same design as the 1896 to 1898 batch of 7th Class engines of the Cape Government Railways (CGR) with their increased heating capacity and type ZC bogie-wheeled tenders, which were later to be designated Class 7A on the SAR.[1]

Transfers and renumberings

After the cessation of hostilities on 1 June 1902, the IMR was transferred to civil control on 1 July 1902 and renamed the Central South African Railways (CSAR). The IMR and PPR 7th Class locomotives were renumbered by the CSAR in the ranges from 373 to 397 and 398 to 400 respectively.[1]

Natal Government Railways

In 1906, three of these locomotives, CSAR numbers 384, 389 and 393, were sold to the Natal Government Railways (NGR), who used them to work on the Harrismith-Bethlehem section in the Orange River Colony (ORC) on the mainline from Ladysmith to Bloemfontein. They were designated the NGR Class L and renumbered in the range from 327 to 329.[1][6]

SAR classification

When the Union of South Africa was established on 31 May 1910, the three Colonial government railways (CGR, NGR and CSAR) were united under a single administration to control and administer the railways, ports and harbours of the Union. Although the South African Railways and Harbours came into existence in 1910, the actual classification and renumbering of all the rolling stock of the three constituent railways were only implemented with effect from 1 January 1912.[4][7]

When all of these locomotives, with three exceptions, were assimilated into the SAR in 1912, they were renumbered in the ranges from 1032 to 1034, 1036 to 1039 and 1041 to 1058, all designated Class 7B.[1][2][4]

Leased locomotives

The first two of the aforementioned three exceptions, ex IMR numbers 106 and 113, later CSAR numbers 376 and 383 respectively, had been leased to Pauling and Company in 1911 for use on a construction contract. They were only returned to the SAR in January 1913 and then received the numbers 1035 and 1040 respectively. These numbers had apparently been reserved for them even though the numbers were not listed in the 1912 renumbering tables.[1][2][4][8]

Classification errors

Two locomotives which returned to South Africa from Rhodesia c. 1915 were incorrectly classified, possibly as a result of their records getting exchanged in an apparent administrative error. Each received the class designation and engine number meant for the other.[1]

- IMR no. 110, the third aforementioned exception, would have become CSAR no. 380 in 1902 but never did, since it had already been transferred to the Beira and Mashonaland and Rhodesia Railways (BMR) at Umtali in March 1901 as replacement for a war-damaged locomotive. In Rhodesia, it was renumbered to MR no. 19. When it was eventually sold back to South Africa and taken onto the SAR roster in 1915, it was incorrectly designated Class 7D instead of Class 7B and renumbered 1355.[1][9]

- In 1915, the sole aforementioned ex RR locomotive was brought onto the SAR's Class 7B roster as SAR no. 949. It had started its service life as RR no. 1 and was renumbered twice in Rhodesia. In the 1901 Rhodesian renumbering it was renumbered to MR no. 8 on the BMR. In the 1906 Rhodesian renumbering it was renumbered again, this time to no. 63 on the Rhodesia Railways Northern Extensions (RRM, operating north and east of Bulawayo). This locomotive was part of the same batch of ex RR locomotives of which some became SAR Class 7D and it was therefore incorrectly designated Class 7B.[9][10]

Class 7 sub-classes

Other 7th Class locomotives which came onto the SAR roster from the Colonial and other railways in the region (the CGR, the NGR, some from the RR and, in 1925, from the New Cape Central Railways) were grouped into six different sub-classes by the SAR, becoming SAR Classes 7, 7A and 7C to 7F.[4][11]

Modifications

Central South African Railways

Beginning in 1904, many of these locomotives were equipped with larger cabs, which gave less cramped working conditions and better regard for the comfort and health of engine crews who worked under the trying conditions of the Transvaal Lowveld. One locomotive, CSAR no. 381, later SAR no. 1058, was also reboilered with a larger round-topped boiler. The reboilered locomotive was reportedly also equipped with Drummond tubes in its firebox, but these were found to be unsatisfactory and were soon removed. The larger boiler enabled the locomotive to take the same load as a Class 8-L2, which was 29% greater than the legitimate load of the 7th Class.[1][3][9][12]

The practice of replacing original boilers with larger boilers of greater weight, capacity and operating steam pressure did not always produce satisfactory results. Considerable success was obtained with such modifications on the CSAR Classes 6-L1 to 6-L3. On the two versions of 5th Class, the fact that they were gradually being replaced on mainline work made the cost of reboilering and modifying the frame unjustifiable. On the reboilered 7th Class locomotive, problems were experienced with overloaded bearings and loose crank pins which led to a decision not to convert any of the others.[1][3][9][12]

South African Railways

During the 1930s, many of the Class 7 series locomotives were equipped with superheated boilers and piston valves. On the Classes 7B and 7C, this conversion was sometimes indicated with an "S" suffix to the class number on the locomotive number plates, but on the rest of the Class 7 family this distinction was rarely applied. The superheated versions could be identified by the position of the chimney on the smokebox. The chimney was displaced forward to provide space behind it in the smokebox for the superheater header.[3][4][11]

Service

South Africa

In SAR service, the Class 7 series worked on every system in the country. They remained in branch line service until they were finally withdrawn in 1972.[3][9]

South West Africa

In 1915, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, the German South West Africa colony was occupied by the Union Defence Forces. Since a large part of the territory's railway infrastructure and rolling stock was destroyed or damaged by retreating German forces, an urgent need arose for locomotives for use on the Cape gauge lines in that territory. In 1917, numbers 1042 to 1044, 1051 and 1052 were transferred to the Defence Department for service in South West Africa.[3][9][13]

These five locomotives remained in South West Africa after the war. They proved to be so successful in that territory, that more were gradually transferred there in later years. By the time the Class 24 locomotives arrived in SWA in 1949, 53 locomotives of the Class 7 family were still in use there. Most remained in SWA and were only transferred back to South Africa when the Class 32-000 diesel-electric locomotives replaced them in 1961.[3][9][14]

Industry

In 1966, two Class 7B locomotives, numbers 1037 and 1040, as well as two Class 7 and four Class 7A locomotives, were sold to the Zambesi Saw Mills (ZSM) in Zambia. The company worked the teak forests which stretched 100 miles (160 kilometres) to the northwest of Livingstone, where it built one of the longest logging railways in the world to serve its sawmill at Mulobezi. These eight locomotives joined eight ex RR 7th Class locomotives which had been acquired by the ZSM between 1925 and 1956.[9]

Railway operations ceased at Mulobezi c. 1972, whilst operation of the line to Livingstone was taken over by the Zambia Railways in 1973. While most of the 7th Class series locomotives remained at Mulobezi out of use, Class 7A no. 1021 and Class 7B no. 1040 were installed as stationary boilers at the Livingstone factory to supply steam for curing wood. No. 1040 was still in use in that role in October 1995, when it was found in steam.[10]

Preservation

Only one member of the 7B class survives in preservation, No. 1056 formerly Imperial Military Railways no. 123. later Central South African Railways no. 389. and later Natal Government Railways no. 328. is preserved at The Railway Museum in George under ownership of TRANSnet. [15]

Works numbers

The table lists all their works numbers and renumbering, except the multiple Rhodesian renumbering of SAR no. 949.[1][2][4][5]

Works No. | IMR No. | PPR No. | CSAR No. | BMR or RRM No. | NGR No. | SAR No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5677 | RRM 63 | 949 | ||||

| 5835 | 128 | 373 | 1032 | |||

| 5836 | 129 | 374 | 1033 | |||

| 5837 | 130 | 375 | 1034 | |||

| 5813 | 106 | 376 | Pauling | 1035 | ||

| 5814 | 107 | 377 | 1036 | |||

| 5815 | 108 | 378 | 1037 | |||

| 5816 | 109 | 379 | 1038 | |||

| 5817 | 110 | MR 19 | 1355 (7D) | |||

| 5818 | 111 | 381 | 1058 | |||

| 5819 | 112 | 382 | 1039 | |||

| 5820 | 113 | 383 | Pauling | 1040 | ||

| 5826 | 119 | 384 | 327 | 1055 | ||

| 5822 | 115 | 385 | 1041 | |||

| 5823 | 116 | 386 | 1042 | |||

| 5824 | 117 | 387 | 1043 | |||

| 5825 | 118 | 388 | 1044 | |||

| 5830 | 123 | 389 | 328 | 1056 | ||

| 5827 | 120 | 390 | 1045 | |||

| 5828 | 121 | 391 | 1046 | |||

| 5829 | 122 | 392 | 1047 | |||

| 5821 | 114 | 393 | 329 | 1057 | ||

| 5831 | 124 | 394 | 1048 | |||

| 5832 | 125 | 395 | 1049 | |||

| 5833 | 126 | 396 | 1050 | |||

| 5834 | 127 | 397 | 1051 | |||

| 5904 | 7 | 398 | 1052 | |||

| 5905 | 8 | 399 | 1053 | |||

| 5906 | 9 | 400 | 1054 |

Illustration

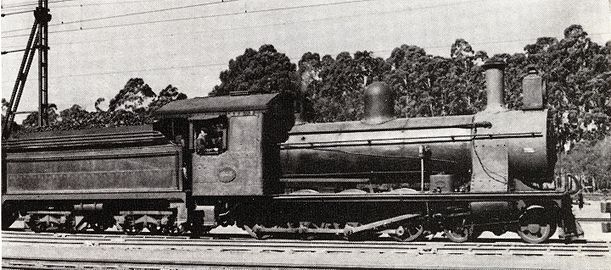

The main picture shows SAR Class 7BS no. 1056 (ex IMR no. 123, CSAR no. 389 and NGR no. 328) at Voorbaai on 4 September 1997. Some of the modifications and applications of the Class 7B are illustrated below.

-

Class 7BS no. 1056 with a 6½ ton coal capacity Type ZC tender, plinthed at Burgersdorp, 8 April 1978 - note chimney location

Class 7BS no. 1056 with a 6½ ton coal capacity Type ZC tender, plinthed at Burgersdorp, 8 April 1978 - note chimney location -

Class 7B no. 1040 grounded as a stationary boiler at Livingstone, Zambia, 28 April 1989 - note chimney location

Class 7B no. 1040 grounded as a stationary boiler at Livingstone, Zambia, 28 April 1989 - note chimney location -

Class 7BS no. 1056 being coaled from cocopans at George, 16 July 1999

Class 7BS no. 1056 being coaled from cocopans at George, 16 July 1999 -

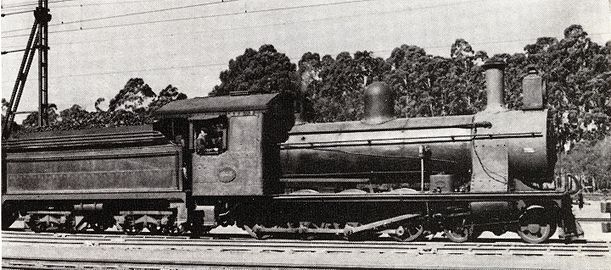

Class 7B no. 1048 with the larger CSAR cab and Type ZC tender with enlarged coal bunker, c. 1950 - note chimney location

Class 7B no. 1048 with the larger CSAR cab and Type ZC tender with enlarged coal bunker, c. 1950 - note chimney location

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Holland, D.F. (1971). Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways. Vol. 1: 1859–1910 (1st ed.). Newton Abbott, England: David & Charles. pp. 105, 120, 122–124, 126, 133–134. ISBN 978-0-7153-5382-0.

- ^ a b c d e Holland, D. F. (1972). Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways. Vol. 2: 1910-1955 (1st ed.). Newton Abbott, England: David & Charles. pp. 32, 139. ISBN 978-0-7153-5427-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Paxton, Leith; Bourne, David (1985). Locomotives of the South African Railways (1st ed.). Cape Town: Struik. pp. 46–48. ISBN 0869772112.

- ^ a b c d e f g Classification of S.A.R. Engines with Renumbering Lists, issued by the Chief Mechanical Engineer's Office, Pretoria, January 1912, pp. 8, 12, 15, 39 (Reprinted in April 1987 by SATS Museum, R.3125-6/9/11-1000)

- ^ a b Neilson, Reid works list, compiled by Austrian locomotive historian Bernhard Schmeiser

- ^ Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (1944). The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter III - Natal Government Railways (Continued). South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, July 1944. p. 506.

- ^ The South African Railways - Historical Survey. Editor George Hart, Publisher Bill Hart, Sponsored by Dorbyl Ltd., Published c. 1978, p. 25.

- ^ Information supplied by John N. Middleton

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pattison, R.G. (1997). The Cape Seventh Class Locomotives (1st ed.). Kenilworth, Cape Town: The Railway History Group. pp. 12–15, 24–32, 38–39, 56. ISBN 0958400946.

- ^ a b Pattison, R.G. (2005). Thundering Smoke, (1st ed.). Sable Publishing House. pp. 42-48. ISBN 0-9549488-1-5

- ^ a b South African Railways and Harbours Locomotive Diagram Book, 2'0" & 3'6" Gauge Steam Locomotives, 15 August 1941, as amended

- ^ a b Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (1945). The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter VI - Imperial Military Railways and C.S.A.R. (Continued). South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, January 1945. p. 15.

- ^ Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (1947). The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter VII - South African Railways (Continued). South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, December 1947. p. 1033.

- ^ Soul of A Railway - System 1 – Part 13: The Ladismith branch, by C P Lewis, Caption 5 (Accessed on 5 December 2016)

- ^ Sandstone Heritage Trust - 2017016 Locomotive status - January 2017. (Accessed on 13 December 2019)

- v

- t

- e

- CSAR 0-6-0ST 1896

- CSAR 4-6-0T 1887

- CSAR Class 6-L1

- CSAR Class 6-L2

- CSAR Class 6-L3

- CSAR Class 7

- CSAR Class 8-L1

- CSAR Class 8-L2

- CSAR Class 8-L3

- CSAR Class 9

- CSAR Class 10 1904

- CSAR Class 10 1910

- CSAR Class 10-2 Saturated

- CSAR Class 10-2 Superheated

- CSAR Class 10-C

- CSAR Class 11

- CSAR Class B 0-6-4T

- CSAR Class C 2-8-4T

- CSAR Class D

- CSAR Class E 4-8-0TT

- CSAR Class E 4-8-2T

- CSAR Class E 4-10-2T

- CSAR Class F

- CSAR Class M

- CSAR Mallet Saturated

- CSAR Mallet Stoker

- CSAR Mallet Superheated

- CSAR Rack 4-6-4RT

- CSAR Railmotor

- IMR 0-6-0ST 1896

- IMR 4-6-0T 1887

- IMR 46 Tonner 0-6-4T

- IMR 55 Tonner 2-6-4T

- IMR 7th Class 4-8-0

- IMR 8th Class 4-8-0

- IMR Reid Tenwheeler 4-10-2T

- IMR Western Australian 2-8-4T

- NZASM 10 Tonner

- NZASM 13 Tonner

- NZASM 14 Tonner

- NZASM 18 Tonner

- NZASM 19 Tonner

- NZASM 32 Tonner

- NZASM 40 Tonner

- NZASM 46 Tonner

- OVGS 1st Class 4-4-0TT

- OVGS 2nd Class 2-6-0

- OVGS 2nd Class 2-6-0ST

- OVGS 3rd Class 4-4-0

- OVGS 4th Class G 4-6-0

- OVGS 5th Class K 4-6-0 1890

- OVGS 5th Class K 4-6-0 1891

- OVGS 6th Class L 4-6-0

- OVGS 6th Class L2 4-6-0

- OVGS 6th Class L3 4-6-0

- PPR 0-4-0ST Natal

- PPR 26 Tonner

- PPR 35 Tonner Portuguese

- PPR 55 Tonner

- CSAR Pankop